Before we land

There are as many Mexico's as there are Mexicans in it.

The Mexico that I knew growing up involved lush gardens within walls, trendy video-gaming consoles, and a trilingual education. This was a sheltered and certainly privileged México. The world within these walls was a very different world than the one outside. Like most privileged Mexican children, fearful of what could happen beyond these walls, I never really ventured on my own outside my house until I was thirteen years old. Crossing those walls meant exposing myself to a world that I'd long been told was dangerous: a violent, volatile place full of bad “hombres” doing bad things. This was a country where most people didn’t look or think like me or my family — a Mexico that was, essentially, unlike myself.

It is percisely that Mexico we are dealing with in this journey: The unjustified margins of México, long misrepresented under the banner of danger. This Mexico appear to be a living contradiction, a relentless opposition between the sacred and vulgar, the past and the present, tradition and progress, and so on. But it is at once much simpler and infinitively complex than that… What is clear, however, is that not two cities, villages, or homes are the same. The richness and diversity of the country are astounding, even when at first glance it would appear globalization has all but paved them flat. As a place, it is much greater than any one person could ever understand. And so, my reflections on México are only approximations far from a pure distillation of the country’s spirit. Nevertheless, it is a search for understanding, not only of the country but of my place in it as well.

I’ll disclaim that despite vowing to steer away from anything “theatre” during my my travells, I inevitably observed the world through the lens of theatre. This enterprise was, after all, framed as “a search for Mexico’s ancestral, theatrical spirit” — an extraordinary opportunity granted by The Julie Taymor World Theatre Fellowship. However, it was also a thoroughly personal rediscovery of the Mexico that I’d known and how it had changed. And so upon setting out on my journey, I promised to empaparme (soak myself) with México, in all its forms, and to allow, with patience, for this experience to seep into my artistic sensibilities. I hoped that, in the end, the journey would condense and transform itself into something which could be shared on stage — it has and continues to do so.

Lastly, I hope that by sharing these brief and impressionistic entries I may be able to discover and reveal not only some unsung wonders of Mexico, but also some surprising part of myself.

Mexico City (CDMX)

To explore the Mexico I don't know, I must first reconnect with the Mexico that I have known.

October 1st, 2016: There’s something oddly welcoming about the unbridled chaos that is Mexico. Flying to the country, one arrives not upon landing but upon the moment one sets foot on the plane; that is so long as there are Mexicans on board. Shortly after takeoff on my connecting flight from Houston to Mexico City, at least six bumbling adults line up for the potty in complete disregard of a lit, seatbelt sign; the bewildered, American steward gesticulating, desperately, at the transgressors’ empty and unbuckled seats. He and I share a sigh and a shrug. I think to myself – “why couldn’t they go before boarding?” – almost immediately recognizing just what an American (or rather, non-Mexican) kind of thought that was. And I realize that my sensibilities are in need of some recalibrating, that is if I want to live and survive in the beautiful chaos of a place that is México.

Mexico City skyline by Insurgentes.

(A chinampa is an agricultural and irrigation system consisting of a series of man-made islands, one prominently used by the aztecs at their ancient capital, Tenochtitlan, limited to an island in the middle of the Lake Texcoco, its basin now completely dried up and occupied by present-day Mexico City). Photo of Chinampas at Bicentennial Park by Yolanda Arango.

As someone from the pint-sized, neighboring city of Cuernavaca, the sprawling goliath that is Mexico City has always seemed like an untamable beast of concrete. However, things seem different now. The morning after my arrival, a friend and I go jogging to the Bicentennial Park near Azcapotzalco, a northwestern delegación (borough) that, having once been more provincial, has been seized by the kind of urban sprawl that knows no patience. Expecting the typical rundown parks common to the brusque conglomeration that is Mexico City, I am pleasantly surprised to see those expectations defied by a state-of-the-art park featuring a waterfront, exercise machines, fields and courts for various sports, a skatepark, an outdoor concert hall, various greenhouses, among other amenities – I am particularly impressed by a modern chinampa.

I am more impressed, however, of seeing capitalinos (Mexico City locals) exercising the park’s offerings. Public parks in the capital have not, for the longest time, been considered as the safest of places for leisure-some congregation. For the first time I, as well as those around me, appear to feel completely at ease in such kind of space; for the first time, I sense the kind of public development that I’d long heard politicians promise again and again; for the first time, I get a sense of some kind of change. Even the name of the city has been officially changed from Mexico D.F. (Federal District) to simply Ciudad de Mexico (CDMX), Mexico City.

The rest of the Sunday afternoon I spend at the Azcapotzalco city center, where local elders dance in pairs to a danzón, while teens practice “dominating” the futbol (soccer) ball. The Casa de Cultura features an art exhibition of stunning, Oaxacan statuettes made of corn husks. From the local Church’s atrium next door, you can hear vocal trills familiar to anyone even slightly familiar with voice training. In the atrium there is a stark cultivation of silence so contrasting to the boisterous streets sounds. I wonder – where are the lines drawn between the silent, solemn Mexico and the loud, cacophonous Mexico?

It is now October 2nd, and the anniversary of the Tlatelolco Massacre, when in 1968 the government sent the national army upon hundreds of students protestors at the Plaza de las Tres Culturas in Tlatelolco just ten days before the opening of the first Summer Olympics ever to be hosted by Mexico, the first Latin American nation to be granted the honor. The students had been protesting against the increased economic and social repression on behalf of a government that, despite putting up an international façade of progress and order, still resorted to aggressive, despotic, and undemocratic methods of government.

Palacio de Bellas Artes, blocked off due to protests.

Exactly thirty years later, today, thousands of citizens march through the city center’s streets (many of which have been purposefully closed by the authorities) in remembrance of an act injustice that is particularly resonant with current issues, such as the unresolved case of the mass kidnapping of forty-three university students in the town of Ayotzinapa. As the streets of the Zocalo are devoid of the usual transit, and while the Mexican flag (where red is meant to symbolize pilled sblood) flies at half mast, my impressions of progress from a day earlier suddenly dissipate as I’m confronted with the parallels between today and third years ago… Progress suddenly seems like an illusion, because beautiful parks and dazzling museums are not solvents for the deeply entrenched issues of impunity and injustice that affect the Mexican people every day of their lives.

As sunset nears, I go to Tlatelolco's Plaza de las Tres Culturas, the place of the massacre. At this plaza situated amidst the three cultures (Aztec ruins, a colonial church, and a modern tenement), there's a candle-lit, flower memorial by the central statue, salesmen offering of books and documentaries about the "true story" of the massacre, and a neo-indigenous prayer circle to the Aztec gods that verges between the sincerely mournful and the irreverently kitsch. Most touching of all is a solemn congregation, much smaller in scale than the massive protests held downtown, held by survivors of the massacre of '68. Almost fifty years later, these men bravely recount the happenings of that day, the wordless arrival of the military, the unrelenting firing of bullets, the persecution of innocents, the terror of those trying to escape, the generosity of nearby homeowners hiding students from the authorities, and the disregard for human life. One of the now-elderly men looks around at the younger generation (one facing its own struggles in their fight for justice), and says: "It may have cost me an eye, but if I were young again," – a sudden pause, silence taking hold of his voice – "I would do it again."

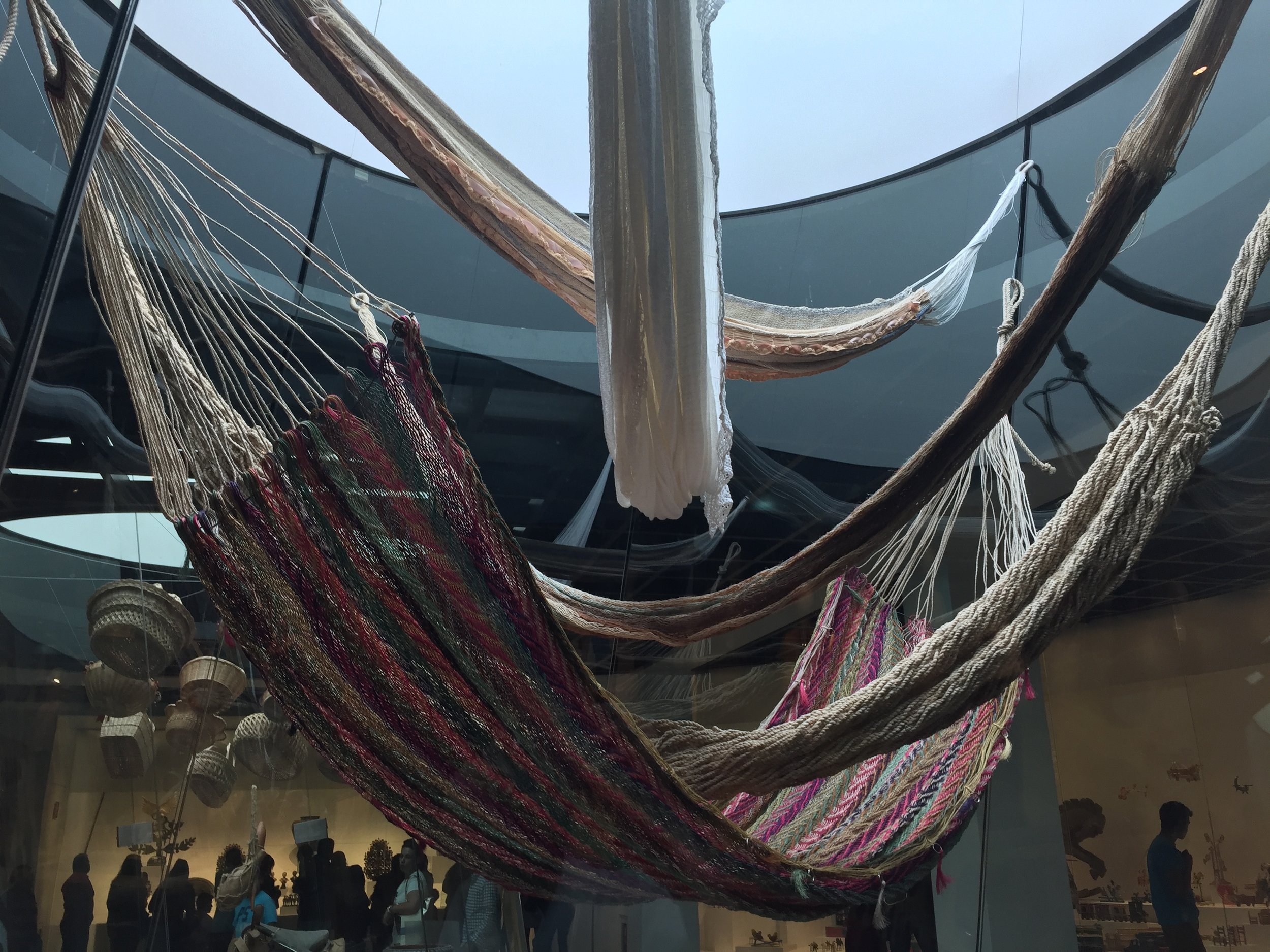

At the end of the day, I find myself thinking back to my visit, earlier that day, to the Museo of Arte Popular. There, the history of traditional textiles may be distilled down to a mere three, natural pigments: grana cochinilla, caracol púrpura, and azul añil. From the mixing of simple colors of carmine, purple, and blue, weavers would dye textiles an incredible number of shades and hues. Perhaps these three colors would be a better fit for the Mexican national flag, a flag that sports a bellicose red for war, a catholic white for purity, and a desperate green for hope. Perhaps it should be a flag not fashioned on imitative emblems of the European colonizers, but on the humble colors of our indigenous heritage. (Did not Benjamin Franklin champion the Turkey over the Eagle?)

Naturally-dyed hammocks at the Museo de Arte Popular.

My third, last, and slower day in CDMX, I share it with some old family friends. Of the family's four "kids", I went to school with the eldest, and my brother with the youngest. I visit the whole family at their new restaurant, for which the eldest, having just graduated from culinary school, has taken the lead from her mother. As each of us two begins our first, "adult" endeavor in our lives, however different they may be, I am struck by how greatly things change over time... And also how little things change: they still offer me dish after dish, and pastry after pastry, only this time it's the daughter, not the mother, making the offer. And what a common pleasure it is in Mexico to just reach into each other's food plates and take a probadita of a bite (yes, this is a stab at my fussy, American friends). It is surprisingly easy to slip back into the local ways, even when I am told that I seem "different", that I speak funny, that I've become a bit of a gringo. Still, this terrace-turned-restaurant feels so strongly of our life in Cuernavaca, our hometown, acting like a small oasis so distinct from the bustle of the big city. Mostly, it feels safe, much like Cuernavaca used to feel a few years ago. Though things, I've heard, have changed... Later that night, I take a hour-long bus trip south, out of the Valley of Mexico and into Cuernavaca, wondering just exactly how things have changed in a place known as the city of eternal spring.

Morelos

Cuernavaca

'Till the last of her mindful days, my grandmother would sit on the hanging chair of the terrace, as she waited, wrapped in her Oaxacan shawl, for her "papá" to come home to her. Time and time again, she would wait — almost timelessly. I would come into her house to the sight of her patient waiting, her gaze fixed on the entrance gates. In time, the light in her eyes faded to nothing, but her presence can still be felt in the empty space of that chair. In the terrace of this old home, built for my abuela by the hands of my abuelo, a home now almost completely abandoned, there is both a serene pulse of life and an unwinding decay of better times.

In a way, this same feeling can be felt throughout the entire city of Cuernavaca. Once renewed for it's tranquility, Cuernavaca has spiraled out of wellbeing in the recent years. It suffers the symptoms of a small town stubbornly striving to be a big city, obsessing with physical and fiscal grown where there is no space for expansion of such kind. The city has betrayed the very essence of that makes it what it is (or rather, was). Its name meaning "horn of the cow" in Spanish and "place amongst trees" in the indigenous Nahuatl, Cuernavaca is now long past its charming days of cows grazing alongside its main avenues. With its political absurdity (the current mayor is a former striker for the National soccer team), economic hardships (half the businesses I knew are gone), precarious safety (highest in the national index for kidnappings), cultural mismanagement (century-old trees of the Jardin Borda decimated for "renovations"), and ceaseless violence (a battleground for competing drug cartels), the city is, tragically, all but a ghost of its former self.

Cuernavaca Cathedral at the city center.

Still, life goes on – people learn to live with fear: Students continue assembling protests against political impunity; a mother still takes her kids to school in spite of rising bus fares; bureaucrats keep stamping useless documents; ambulant salesmen still offering trinkets for a few pesos; kids play futbol at the zocalo's esplanade; two policemen parents bless their goodbye daughter as she leaves for the highway; and my grandfather still hustles insistingly through his affairs... Life finds its time of day. Still, at nighttime, the streets are nearly empty except for the palpable fear of being taken captive by the well-known, hidden dangers of the city.

Hardly a city of eternal spring anymore, Cuernavaca sees me leave once more.

Tepoztlán

A pueblo magico a state-granted denomination for villages that offer visitors a "magical" experience – by reason of their natural beauty, cultural riches, or historical relevance. More on this later...

Before leaving the state of Morelos, I take a day-long deviation to the Pueblo Magico of Tepoztlán, located nearly an hour away from Cuernavaca and in a smaller valley surrounded by eerie mountains. In recent years, Tepoztlán become a hub for artists, hippies, and ecotourists. There are many extraordinary people who've found their lives deviated by the mesmerizing mountain of El Tepozteco: Mystics and paranormals have claimed that it is otherworldly in origin; artists have mused of its belly as the haven of the banished gods of the Nahua; geologists have come to decipher the mystery of its incomparable ruggedness; and daredevils have latched to its cliffs in a vigorous defiance to death... And yet, it is those who stand simply by the mountain's skirt, those living their lives in a humble acceptance, in a trickling awe of its presence — it is those the ones that he considers most extraordinary. These are the locals of Tepoztlán, who still follow old traditions, many of which come to life in the fiestas. I make a vow to return at such a time.

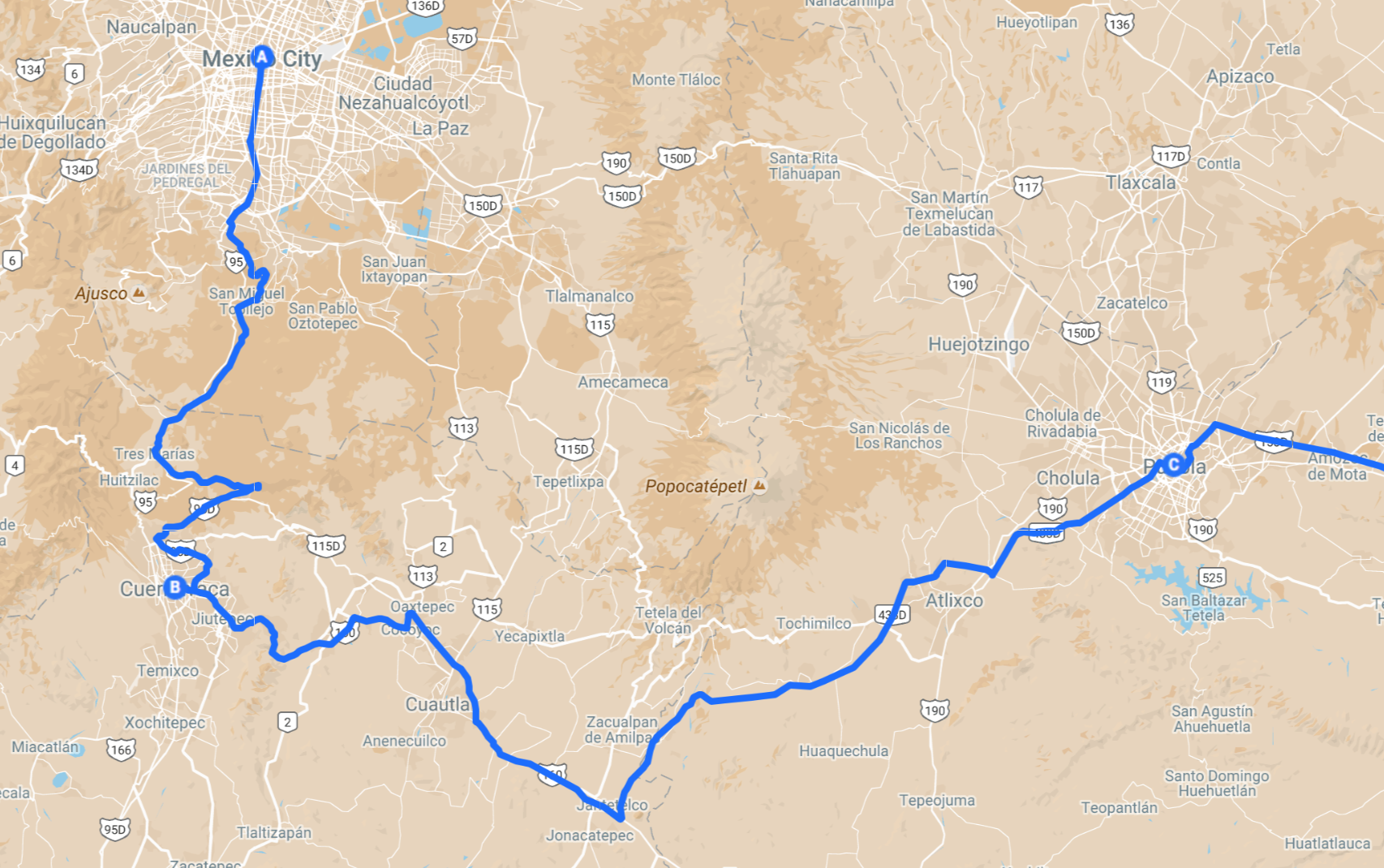

After a brief, three days of patient rekindling with my home state, I pack my clothes in a sugar sack (hopefully leaving a sweet scent ), and I leave for the state of Puebla, my last stop in the central region (the Mexico I know) before heading further South.

From Mexico City, to Morelos, to Puebla

Puebla

Shared among the central states of the country is the magnificent view of the Popocatépetl, an active volcano stretching 17,802 ft in altitude. Legend says that the fierce warrior Popoca returned home from battle to find his beloved bride dead. Heartbroken, Popoca offered his body and his bride's to the gods, which then transformed into two adjacent volcanoes: Iztaccíhuatl, the dormant woman, and Popocatépetl, smoking mountain. On the bus to from Morelos to Puebla, I can see the Popo still fuming in anguished love. Coincidentally, the is playing film by Cirque du Soleil in which a man performs dazzling yet ostentatious acrobatics over some suggested volcano. Contrasting it with the view of the Popo just outside my window, I think of man's constant intent on placing himself at the center of admiration over its surroundings. This man conquers a volcano with his physical prowess but develops no relationship, or respect, for the giant he claims to tame. The counterfeit awe in this display does not begin to compare with the humble awe that comes from gazing at the real volcano. How can one suggest such a feeling on the stage?

Cholula

Outside of the Church of La Virgen de los Remedios, on top of the Great Pyramid of Cholula, overlooking the city and a clouded Popocatépetl in the distance.

In the city of Puebla, I am received by my padrino (godfather) who lives here and works in the yellow-hued, sister-city of Cholula, where he takes me that evening. Both cities are famous for their vast number of churches, having been a bastion of conservatism since colonial times. Today, it is now one of the most progressive and developed states in the republic. Nevertheless, it's colonial and indigenous past can be seen in its architecture and devout followers. My padrino says one can recognize people from Cholula because many still carry (unlike most Mexicans) an indigenous surname.

At lunch time, as I'm taking a bite of my enchiladas, I hear the sound brass instruments, the kind used in religious processions, emanating from the streets. I rush out to find the patron saint of one of the barrios (each quarter of the city has it's own patron saint, with its own celebration) being paraded around. The procession is meager, but it leaves me a taste of the kind of theatricality latent in the old Mexico, a taste that develops into a hunger that not even a good mole poblano can satisfy. "This is procession is smaller," says the owner of the fonda, "We celebrated St. Francisco de Assis a few days ago. You missed out on that..." Half hurt by the lost occasion, I think to myself – "Patience."

Transformed from a pre-Columbian temple to the God Quetzalcoatl to religious center for the Catholic Virgen de los Remedios, the Great Pyramid of Cholula is a physical example of how the base of one religious tradition was used to build upon another (a dynamic that I'll surely continue to encounter through my travels). Though it has become covered in dirt and overgrown with grass, the pyramid is the largest in the world, Old and New.

Even churches in Cholula are bewitched with a cyclical collision between of the ancient and the sacred, there is still a sense of life pulsing through the atriums... Lovers can be overheard discussing under the pine trees what it means to be in love. In general, the whole of the church in its resonant acoustics, its eerie lighting, its spatial symmetry, its stunning views, and its ample atrium is a thoroughly fertile land for the theatrical act. The question is: how willing are leaders and patrons to let the lines between the sacred and the theatrical be blurred?

Lovers discussing love underneath a tree.

Puebla

Church-seeing is, admittedly, not of great interest to me. That's a bit of a pity given all the stunning, colonial-era churches found throughout the country and especially Puebla. One may think this distaste is because I am not a religious person, despite coming from a mostly catholic family (with a few heretics here and there). But the truth is that, as much symbolic force there may be in these religious relics, I simply see little life force within the clustering walls of these churches... (Or so I thought)

"You must visit the Capilla del Rosario (Rosary Chapel) – it's stunning," my padrino tells me as he drops me off in the city center. "So is the Biblioteca Palafoxiana" (allegedly the first public library in the Americas). "Also, the McDonalds has the best view of the zocalo..."

Biblioteca Palafoxiana.

After a few minutes of strolling through the cathedral, where women pray for permission to enter and kiss the hands of suffering christ figures, I stumble upon the famous Biblioteca Palafoxiana, which, housed within a Casa de Cultura, is hosting in its courtyard some pseudo-Polynesian dance workshop (why?). The library was founded in 1636 by the Bishop of Puebla, having said that "there should be in this city and kingdom a public library, where all sorts of people will be able to study as they wish." However, one must pay to enter this library, and cannot sit and read anything, let alone the books in the collection. One must only come in to admire the collection from afar... So much for a public library.

Frustrated by the "preservation of our heritage", I am drawn by some rumbling zapateo, the sound of stomping shoes, coming from the courtyard. There, a group of kids dance the folklore of their surrounding communities, and they are stunning. In their first dance, a young bride in a white dress and a much, much younger groom (no older than seven) in a primarily black suit and sombrero hold hands while tapping their feet as if running through the wedding aisle. Surrounding them, there's a cohort of men dressed in the same fashion as the groom, each of them holding a handkerchief of a different color: orange, green, teal, etc. In the end, the men take off their sombreros, revealing they are actually girls in play pretend.

In the next dance, boys and girls dance in pairs, dressed in traditional suit-and-sombreros and vibrant dresses, respectively. The girls take hold of their skirts and flutter them quickly, back and forth, showcasing the beauty of their uniquely colored dresses. For the boys, it's a zarape (a multicolored, Mexican shawl) what adds a particular touch of color to their garb. Though some of the almost pubescent boys are naturally not the most skilled dancers, some of the young lads show promise and even virtuosity.

For the last dance, a group of sixteen boys and girls (this time, each gender uniformly dressed) dance with and around an empty bottle that the imagination may fill with anything from water to, most likely, hard liquor. Some may be quick to call this an inappropriate subject, the struggle between women and the bottle. However, the dance ultimately speaks the most to those who watching – the adults. These colorful, moving tableaus represent moments of traditional life in the country: vignettes of courtship, marriage, struggles, and joy. In this sense, this is a pure, act of theatre. And much like masks or caricatures, children are much more lively (dare I say truthful) when it comes to play pretend, also allowing for some distancing from mere realism... Having said all that, the dance is most importantly, and most wonderfully, full of joy.

I take a stroll through the old downtown, get some cinnamon-dusted churros, and walk past the atrium of the Rosary Chapel, where two boys partake in the perhaps the most sacred of Mexican activities – futbol. Though I'm half kidding, the sport has become an important and certainly ritualistic element of Mexican life, just as these boys playing goalie before the church may attest.

A disbeliever gazing upon the intimidatingly tall doors of church, I force myself through through them, as I mentally prepare myself for some potential boredom and occasional yawning. I must try to see Mexico from all its angles, and religion, secular as the state is supposed to be be, is one of them. The inside is, in my eyes, just like many other churches and ex-convents of the country, ornamented saint figures adorning the walls in golden tableaus. It is beautiful – there's no denying that. But, oh, how I wish the space could be used otherwise.

Further ahead lies the famed chapel dedicated to Virgin of the Rosario, who stands in a splendid, golden altar. A volunteer guide, who offers explanations in exchange donations, talks a group of visiting, middle-aged women, some of them erudite of all things catholic. Thinking of the sixteen dancers from earlier, I ask him about the symbolism behind the eight pairs of saints surrounding the virgin. "Eight is the the number of infinity and of the Virgin Mary," responds a clearly devout woman. People know what people know... Among his many explanations, the guide says that "the Virgin of the Rosary is the protector of travelers and voyagers, raising waves against enemies in one's journey..." How very coincidental.

As the guide moves the visit forward and the chapel begins to empty, I see a man snapping a picture of his daughter before the altar. She smiles, sporting of big, purple, Minnie-mouse bow over her head. The whole set up is, I think, rather silly. The church has yielded solemnity in favor of tourism. And then, with a sudden change in his energy, the man grabs his daughter in arms, looks up at the virgin, and says "my dear virgencita, thank you for my greatest treasure, this little one that I hold here in arms before you..."

I am shattered.

By some divine, unexpected inspiration, I get on my knees and begin praying to the figure before me. I barely remember how to pray, but still – I do it. Thinking of my mother and her fears for my well being in an increasingly dangerous country, I ask for the Virgin's protection. I am weeping. In return, I promise to carry out my mission, however and wherever it may take me... I cross myself, the motion feeling beautifully strange and familiar at the same time. I stand, look at her magnificent figure, and walk away, leaving with, if anything, belief in a single conviction.

To lighten things up, above (from left to right) are some of the other typical elements of Puebla: the famous blue and white talavera colors, traditionally used in local ceramics as seen from cable railway overlooking the city; four types of delicious mole poblano: rojo (tomato), blanco (white nuts), negro (heavy on the chocolate), and pipián (sunflower seeds); and, lastly, a calming cup of jade oolng that I shared with an ambulant salesman at the Barrio del Artista..

To close my time in Puebla, I attend an old friend's opening night in a new devised work called The Rhetoric of Silence. It takes place in large loft repurposed as a performance space overlooking the city streets. I come in as skeptical as always about the Mexican theatre, which has yet to find an affecting voice or space. The piece, however, is surprisingly captivating, mainly due to the actor's endearing performances and the profound (if sometimes pretentious) questions posed by the text. Nonetheless, I am particularly impressed by these theatre-makers of my same generation. After the performance, I join my friend and the rest of the cast for dinner, and we chat about theatre and life in Mexico, staying awake until the early hours of the morning.

Reinvigorated in my questions and my doubts, I leave that following day towards the state of Oaxaca. As I to leave the Mexico that I do know to encounter the Mexico that I don't, I think of the promise that I made in that chapel... I grasp for an imaginary rosary around my neck, looking for courage as I proceed into the unknown.